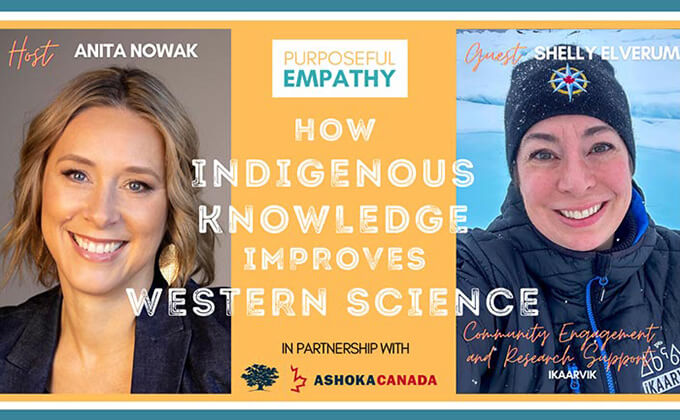

Shelly Elverum

Ikaarvik

Pond Inlet, NU

Sector Impact

Children & Youth

Civic Engagement

Economic Development

Education

Environment & Sustainability

Human Rights & Equality

Indigenous Peoples & Reconciliation

Science & Technology

THE ARCTIC’S ORIGINAL SCIENTISTS

The Challenge: Climate change is rapidly altering once-stable Arctic landscapes as their Indigenous inhabitants contend with the ongoing devastation of racist colonial policies. The region’s youth in particular are vulnerable to food and housing insecurity, scarce employment, and low graduation rates. Inuit fear that their sophisticated traditional knowledge systems may no longer safeguard their survival.

The Solution: With Ikaarvik, Shelly Elverum is engaging Inuit youth to reclaim their roles as the Arctic’s first scientists, capable of managing resources, determining their cultural and economic futures, and adapting to rapid climate and cultural change in the North.

A new knowledge economy in the Canadian Arctic.

Shelly Elverum supports the recentring of traditional Inuit knowledge systems into Western science, in the process creating new roles for Inuit youth as valued members of the Arctic’s social and scientific communities.

The Inuit are the Arctic’s original scientists, says Shelly Elverum, with a sophisticated system of cultural and place-based knowledge — called Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit or “IQ” — that has developed and evolved over millennia to safeguard survival and social harmony. Scientific techniques, including observation, monitoring and testing, she argues, have roots in traditional Northern Indigenous knowledge systems.

But that survival and social harmony are under threat, challenged by climate change, and by the ongoing and devastating impact of Canada’s residential schools and other racist colonial policies. The Inuit — and particularly Inuit youth — are vulnerable to the region’s high rates of food and housing insecurity, low graduation rates, scarce employment opportunities and poverty, all of which contribute to suicide rates that range from 5 to 25 times the Canadian average.

Shelly grew up in the Canadian Arctic, only vaguely aware of her whiteness and the privilege it afforded her. Only as an adult, in southern Canada, did she realize that she had been the only white student in a residential school, and that, unlike her, her Inuit classmates were regularly streamed out of academic programs. Mindful of the ways she had profited as a settler from these racist systems, she returned to the region to begin a conversation with the Inuit about how to best serve in the community.

In 2013, Shelly began teaching environmental technology at Nunavut Arctic College. But instead of training Inuit students in supporting roles as boat drivers or sample collectors for southern scientists, she insisted on developing their skills as scientists in their own right.

Outside the college, Shelly and her students co-created a new program: Ikaarvik (which means “bridge” in Inuktitut), reorients scientific research and agendas in the area from a southern and settler focus to a northern perspective that focuses on the region’s priorities, strengths and young people. Ikaarvik youth researchers coined the term “ScIQ,” to describe the incorporation of Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit into Western science. The result? Better, more relevant, science that empowers Inuit youth and the communities they live in.

By 2019, Ikaarvik had trained more than 750 early-career scientists in the basics of community-based research, meaningful engagement within Indigenous communities, and the utilization of Indigenous knowledge. The Kluane and Champagne-Aishihik First Nations communities in the Yukon are adapting the model for their own use. Internationally, Ikaarvik youth are working with the Arctic Council’s Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment and the International Institute for Sustainable Development’s Circumpolar Young Leaders program.

Ikaarvik is expanding rapidly, attracting increasing numbers of students, funders, and partners, and extending programming to address mental health, young women’s empowerment, and cultural empowerment.

As for herself, Shelly’s long-term goal is to become obsolete, leaving Ikaarvik entirely in the capable hands of Indigenous youth.