English

By Lis Suarez-Visbal

The global fashion industry, valued at trillions of dollars, employs millions of workers around the world—from cotton farms to factory floors and, eventually, recycling centres. While developing countries handle much of the labour-intensive production, developed nations play an integral role in distribution and waste management. Despite its economic power, fashion is under increasing scrutiny for its environmental and social issues, including resource depletion, hazardous chemicals, and widespread waste, as well as the exploitation of workers in unsafe conditions.

The rise of fast fashion, characterized by overproduction and the rapid turnover of cheap clothing, worsens these issues by encouraging exploitative practices for quick profits. As consumer awareness around sustainability grows, the industry faces a crucial question: Can it embrace environmentally friendly practices without exacerbating social inequalities?

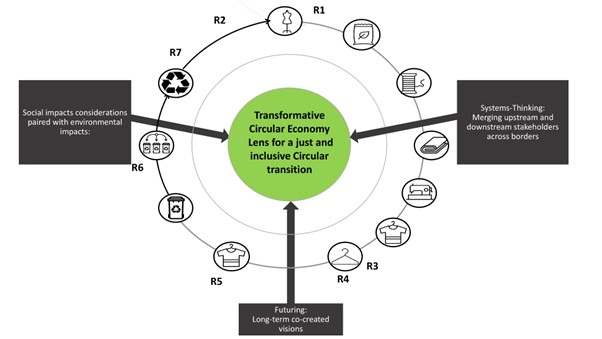

One promising path is the adoption of Circular Economy (CE) strategies. By focusing on minimizing waste and extending the life of products through resale, repair, and recycling, circularity offers a model that could decouple economic growth from resource extraction. Yet, as Ashoka Fellow and Utrecht University researcher Lis Suarez-Visbal’s four-year study, supported by the Laudes Foundation, reveals, the social impact of these new business models is still poorly understood.

The textile and apparel value chain is vast and complex, spanning continents from raw material extraction to manufacturing, retail, and disposal. It plays a significant role in the economies of developing nations, where garment production provides employment for millions. However, workers in this sector, particularly at the bottom of the chain, face severe economic and social vulnerabilities, with limited opportunities for upward mobility.

For many workers, the reality is grim. Human rights violations, including forced labour and unsafe working conditions, are widespread. Women—who form the majority of the garment workforce, from extraction to the end-of life value segments—frequently suffer from wage discrimination, gender-based violence, and lack of access to leadership roles. Many workers are paid less than a living wage, are forced to work long hours, and lack basic labour protections. As brands seek lower prices, the most vulnerable people at the bottom of the chain bear the brunt of these demands. Furthermore, workers at the end of the value chain are mainly informal workers, with no social protection, no stable income and prone to all sort of pollution harmful to their health and wellbeing.

The Circular Economy aims to eliminate waste by keeping materials in use for as long as possible through strategies like reducing production, reusing materials, repairing goods, and recycling products. CE principles seek to decouple economic growth from resource consumption, prioritizing sustainability while also creating jobs.

In the textile and apparel value chain, circular strategies are gaining momentum. Companies are beginning to adopt business models that promote garment rental, resale, and repair services. Brands such as Patagonia and The Renewal Workshop have made repair and resale central to their strategies, while fast fashion giants like H&M and Zara have launched take-back programmes and recycling initiatives. Yet, these circular strategies, while promising, remain limited in scope and often serve wealthier markets.

While circular strategies offer environmental benefits, their social impacts are less clear. The research led by Lis Suarez-Visbal found that many CE jobs—such as those in repair, resale, remanufacturing, and recycling—are characterized by low wages, gender-pay gaps and job insecurity. This trend was observed across multiple countries, including both developing economies like India and developed ones such as the Netherlands and Spain. These circular jobs often replicate the same precarious conditions found in traditional linear production models, with marginalized groups, such as migrant and informal workers, disproportionately affected.

The research underscores the need for circular strategies to address both environmental and social challenges. Without deliberate efforts to improve working conditions, the shift to circularity risks replicating the same inequalities the industry is already grappling with.

To achieve a fair and inclusive transition to a circular apparel economy, businesses must fundamentally rethink their strategies. The research highlights several key recommendations: implementing long-term employment contracts, ensuring fair compensation through living wage policies, addressing gender disparities in the workforce and enabling social dialogue. Circular strategies should go beyond waste reduction to create high-quality jobs that offer economic stability for workers. Integrating social justice into sustainability goals is essential, with companies prioritizing worker well-being alongside their environmental impact.

Transformative Just Circular Economy Lens. Credits: Lis Suarez-Visbal

Governments also have a pivotal role to play. By enforcing international labour standards and mandating human rights due diligence, they can help protect vulnerable workers. Policies such as Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR), which hold brands accountable for their products’ entire lifecycle, could ensure that circularity benefits both the environment and the people involved in production and recycling across borders.

A future where the fashion industry fully embraces circularity while ensuring social equity is not only possible but necessary. By integrating principles of fairness into their circular strategies, businesses, governments, and workers can collaborate to transform fashion from a source of exploitation into a force for sustainable development. In doing so, the industry could lead the way towards a future where no one is left behind.

Discover more about the project at www.uu.nl.

For more information on her research “Assessing and improving the social impacts of circular strategies in the Apparel Value Chain,” Lis Suarez-Visbal can be contacted at l.j.suarezvisbal@uu.nl.

This article was also published by FashionUnited, September 2024: Transforming fashion: The social impact of circular strategies in the apparel value chain

By Mark Abbott & Martin Ryan

From self-driving cars to advanced medical diagnostics and natural language processing, AI unlocks new horizons of possibility, addressing complex problems and driving innovation at an unprecedented pace. As AI technology evolves, it holds boundless potential to revolutionize how we work, communicate and interact with each other and the world around us.

But as we seek to unlock the potential of AI and other transformative technologies, we need to make sure we’re designing and implementing them in a manner that is purposeful, inclusive, sustainable and responsible.

Realizing this vision is not solely a regulatory challenge, it’s a human and a cultural one. This means we will require new social infrastructure to help us manage the inherent tensions created by these powerful and already pervasive technologies.

In the past decade, Canada’s largest metropolitan areas – Montreal, Toronto, Vancouver, Ottawa-Gatineau, Calgary and Edmonton – have become increasingly prosperous. While these regions are home to 47 per cent of Canada’s population, they created approximately three-quarters of all new jobs between 2016 and 2020. In stark contrast, some rural and remote communities have not recovered employment from the 2008-2009 global recession. This economic disparity is more than a statistic; it’s a catalyst for a widening political divide, threatening the fabric of our country.

Rural inhabitants, who often face limited opportunities, can feel neglected by policymakers in urban centres. This sometimes leads to frustration and anger, which contributes to heightened political polarization.

Canada’s current political divides are largely based on the rural-urban split. In the 2019 Canadian federal election, the median population density for the 157 Liberal ridings was more than 38 times higher than that of the 121 Conservative ridings. Research by professors at the University of Calgary and Western University found that there is “clear evidence that Canadians are currently experiencing the most profound urban-rural divide in support for the major political parties in the country’s history.”