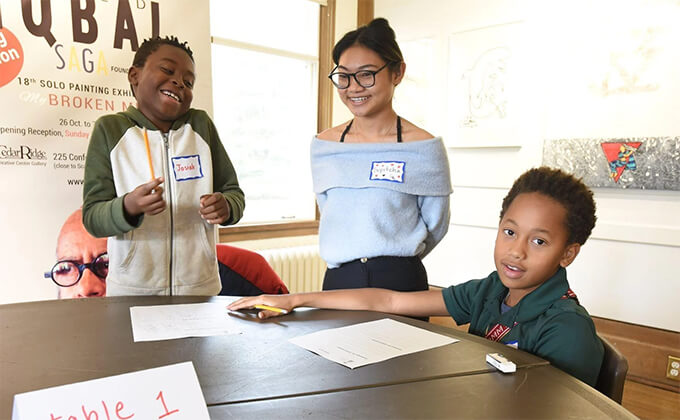

When parents feel respected, heard, and equipped with tools to celebrate their community and culture, they are more likely to engage in their children’s learning.

With The Reading Partnership (TRP), educator and social entrepreneur Camesha Cox is redefining the role of racialized and marginalized parents and caregivers as empowered partners in their children’s literacy.

Teaching all our kids to read

The facts, as Camesha Cox lays them out, are stark: “We know that if a kid is struggling to read by third grade, the likelihood of them catching up is slim to none without targeted interventions. We know by kindergarten which kids will struggle to read by Grade 3. We know that, in Toronto, Black, Indigenous, and racialized children, kids who live in poor neighbourhoods, and kids who are being raised in low-income homes are falling behind at highly disproportional rates. We know that those rates have skyrocketed since COVID-19. And we know that these disparities in literacy have devastating educational, economic, and social consequences.”

And what is our systemic response to those facts?

Camesha, founding director of The Reading Partnership (TRP), pauses. “We don’t have one,” she says. Camesha created TRP as a direct response to the systemic failings of local school systems to teach all the kids, in all of their classrooms, how to read and write using evidence-based strategies and interventions.

TRP, which was founded in 2011 in Camesha’s Toronto community of Kingston-Galloway/Orton Park, partners with school boards, early learning centres, and other community organizations to recruit and train local educators, equipping them with outreach tools to engage with families and communities. Its cornerstone Reading Partnership for Parents (RPP) program is a free, weekly, play-based, holistic literacy program that uses evidence-based approaches to help parents learn the skills they need to teach their kids to read. The Reading Program On Demand (RPOD) is an asynchronous version of RPP that allows families to move through the curriculum at their own pace.

These programs, explains Camesha, aim to repair the relationship between Canadian education systems and Black and other racialized communities — including parents and guardians, who often come to the program with the baggage of their own negative educational experiences.

Other TRP programs include Kids ReadTO, a virtual book club for kids ages 9 to 12 across the GTA, where participants get to meet their favourite authors during live Q&As. 360° Stories is a writing workshop for young creatives, who develop the stories they want to tell, and then are thrilled to see their work published in an anthology. “They leave the program published authors, celebrated by their friends, family, and community members at a book launch,” says Camesha.

TRP also provides families with a “Lit Kit,” which includes all the tools necessary to promote early reading success for kids at home and in the classroom — like decodable TINY TALES books featuring diverse characters and stories. Importantly, Black and racialized kids and their parents see themselves reflected in literacy materials.

“TRP’s tested and proven programs help kids grow into literacy heroes,” says Camesha. “Children leave our programs more capable and confident in their literacy skills, and better prepared to reach their potential.”

Highlights from the Network

Celebrating Community Impact: Camesha Cox at the Toronto Community Champion Awards

‘360° Stories Online’ Empowers Young Writers to Create, Illustrate, and Publish Their Own Stories

By combining digital skills development with Indigenous knowledge systems, Alejandro Mayoral Baños is empowering the next generation of Indigenous technologists.

The Indigenous Friends Association collaborates with tech firms to shape opportunities for emerging Indigenous technologists to thrive within the sector.

Decolonizing digital spaces

Canada’s First Peoples have inhabited Turtle Island for millennia. But that doesn’t mean that Indigenous peoples are “of the past” when it comes to tech, says Alejandro Mayoral Baños. In fact, he says, the tech industry desperately needs to incorporate Indigenous worldviews to sustain itself in a global future shaped by the climate crisis.

The founder of the Indigenous Friends Association has made it his mission to build bridges between the tech sector and Indigenous communities, creating sustainable pathways for Indigenous youth to find culturally aligned careers in tech. In the process, says Alejandro, the IFA aims to create a more collectivist, equitable, and sustainable tech sector by incorporating Indigenous ethics, knowledge, and values.

The work is needed: More than three-quarters of Indigenous youth living remotely see no opportunities for tech training in their communities. Indigenous workers represent only 2.2% of Canada’s digital technology workforce, reflecting the sector’s struggles to meaningfully incorporate inclusive and diverse human resources practices.

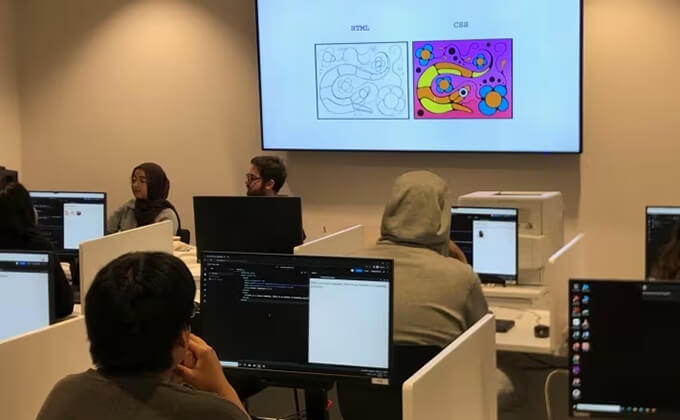

To train Indigenous youth in competencies like UX design and web development, IFA runs the introductory, four-week INDIGital course and the more comprehensive, 30-week IndigiTECH program. These free tech education programs combine face-to-face and online learning that integrates skills development with healing sessions with Indigenous Elders and Knowledge Keepers. For example, the programs incorporate learning circles, prioritize collective wisdom, and focus on Indigenous self-determination and digital sovereignty over knowledge extraction and individualism.

IndigiTECH graduates are eligible for internships with IFA partners — including companies like Shopify, Salesforce, Interac, and CIBC, among others. Crucially, IFA supports its learners and interns with access to mentors and Elders, as well as childcare, food stipends, laptops, and other resources they need to successfully complete the program. The IFA also collaborates with technology firms to develop internships and train recruitment teams. Academic partnerships with researchers from York University and Toronto Metropolitan University build the evidence base for IFA’s advocacy and the effective implementation of its programs.

The IFA is also developing i-ConnectED, a cutting-edge educational platform that delivers course content and instructor communications directly through popular social media channels like WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger, effectively engaging students on the digital platforms they use every day.

Digital technology says Alejandro — who maintains relationships and connections with Totonac communities in Mexico — is increasingly central to Indigenous cultures. “In communities always on the move because of colonization, and now climate change, the mobile phone is the only way for many people to connect with their cultures, or to preserve and speak their languages. Digital technology increasingly aligns with oral traditions.”

As Indigenous cultures adapt to incorporate the strengths of digital technology, Alejandro is building, with the IFA, a world where tech can similarly adapt to the strengths of Indigenous worldviews.

Highlights from the Network

Blending Indigneous Knowledge with Digital Tech ft. Alejandro Mayoral Baños

Scott Stirrett’s Venture for Canada is fostering entrepreneurial skills in thousands of young Canadians.

Venture for Canada is transforming Canada’s entrepreneurial landscape, creating a more equitable and resilient future for everyone.

Transforming Canada’s entrepreneurial landscape

Everyone in Canada needs to be more entrepreneurial, says Scott Stirrett.

But Scott, the founder and CEO of Venture for Canada (VFC), doesn’t mean that every Canadian needs to launch a multinational startup. Rather, he envisions a country where everybody has the skills to identify and act upon opportunities to create value for others — in business, public policy, education, entertainment, or any sphere that creates positive impact.

“As the world becomes more volatile and uncertain, entrepreneurial skills like creativity, collaboration, critical thinking, and navigating uncertainty are becoming increasingly important,” says Scott. Through VFC, he’s actively working to create an entrepreneurial culture in Canada, one that will allow us to face and address wicked problems like climate change, barriers to Reconciliation, a stagnant economy, inequality, and an aging population, among others. Venture for Canada alumni are creating impact across the country, whether that is developing large-scale energy projects with First Nations or raising tens of millions of dollars to build leading technology companies.

“Research shows that the best way to learn how to be entrepreneurial is to work in a small business, where you can get practical, hands-on experience problem-solving in a variety of settings,” says Scott. To that end, VFC facilitates a variety of paid, work-integrated learning opportunities that support both youth and the small businesses that employ them. In 2022 alone, VFC facilitated 3,900 work-integrated learning experiences at more than a thousand Canadian startups and small businesses.

Accessibility and inclusion are core pillars in VFC’s philosophy. As Scott points out, it’s much easier to be entrepreneurial if you have access to capital, mentors, networks, safety nets, and other resources historically less accessible to marginalized communities. In 2022, 71% of VFC’s program participants identified as racialized, 52% identified as women, and 9% identified as 2SLGBTQ+. Within their employer network, 47% of the businesses VFC supports are majority owned by women and 17% are majority owned by people who identify as racialized.

As it grows, VFC is broadening its vision to develop partnerships with Canadian colleges and universities, as well as with governments at all levels to explore how policy can best support entrepreneurs. Within a decade, Scott aims to reach 25,000 young Canadians annually with VFC programming. His overarching vision? “A Canada that is more economically inclusive and prosperous, more ambitious and risk tolerant, and willing to try new ideas that benefit everyone.”

Highlights from the Network

Every young person has the right to safe, adequate, and affordable housing. Youth homelessness can be prevented, and shouldn’t happen in a caring and prosperous society.

A Way Home Canada has sparked an international movement to end youth homelessness, breaking down silos and sectors to co-create communities where every kid has a safe place to call home.

A preventive approach to youth homelessness

Solving youth homelessness won’t happen by providing more and better shelters, soup kitchens, or transitional housing. It’ll happen by preventing kids from becoming homeless in the first place.

That’s the simple, yet profound, premise behind A Way Home Canada, a national coalition that’s reimagining solutions to youth homelessness through transformations in policy, planning, and practice. Ashoka Fellow Melanie Redman is AWH’s cofounder, president, and CEO.

Preventing youth homelessness — not to mention homelessness writ large — says Melanie, requires creativity, experimentation, and measurement. “We want evidence to drive all our solutions.” To that end, AWH has teamed up with the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness at York University to create the Making the Shift (MtS) Youth Homelessness Social Innovation Lab, which is a Government of Canada Research Tri-Council Networks of Centres of Excellence. In 2021, Making the Shift also received the designation as a Geneva UN Charter Centre of Excellence. The lab, says Melanie, is continually trying, innovating, failing — and succeeding — in real time with the goal of building up a solid knowledge base of solutions to prevent homelessness.

AWH has also created the Roadmap for Ending Youth Homelessness, a conceptual framework that defines and provides practical examples of different prevention strategies, as well as who’s responsible at the systems level for each intervention and how they can be part of the solution. The framework is part of AWH’s holistic approach, which recognizes that preventing youth homelessness is a collective effort that requires breaking down the silos between key actors — including young people with lived experience of homelessness.

“When we consult with these youth, they can list, for every stage of their journey into homelessness, multiple interventions that would have helped them and their families stop that trajectory. And so, our focus is very clear. We need to provide wraparound supports and interventions, for as long as necessary, to bolster young people and their families and stop that slide into homelessness. And for those who do end up homeless, the goal is to get them out, and then prevent them from ever falling into that situation again.”

AWH Canada has sparked an international movement, with branches in the United States (launched at the White House in 2016), Australia, the UK, and several European countries. This international network, says Melanie, “is a wonderful platform for knowledge exchange. We can look at see what jurisdictions around the world are doing, and adapt those ideas for communities and contexts.” She cites Wales’s “duty to assist” mandate, which enshrines public agencies to work together to take fulsome action within a certain timeframe once they become aware of a young person facing homelessness.

“As a result, homelessness has dropped dramatically. So how can we adopt that duty to assist in Canada — and how might we shift it to a duty to prevent? It’s exciting.”

Highlights from the Network

By shifting focus, funding, and agency to at-risk, remote, and Indigenous communities, SeeChange Initiative fosters more effective, efficient, sustainable, and culturally appropriate models of aid.

SeeChange Initiative’s CommunityFirst approach envisions a world where communities are active, effective agents of their own humanitarian and health-crisis responses.

A radical revision of the global aid system

COVID-19, tuberculosis, Ebola, Zika: When a health crisis hits a remote or Indigenous community, what usually happens?

The usual pattern, says Rachel Kiddell-Monroe, is that a major player in the humanitarian aid industry parachutes in to implement an external, cookie-cutter solution; wrings its hands and wonders why the crisis persists; and then doubles down on its efforts.

It’s a vicious cycle, perpetuated by a global aid system rooted in colonialism. With SeeChange Initiative, however, Rachel proposes a radical reimagining of that system: one that shifts power, funding, design, and implementation directly to the communities facing crises. SeeChange Initiative works globally to support communities in creating their own health-crisis responses. It also cooperates with established humanitarian organizations — for example, Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières — to demonstrate the effectiveness of community-led solutions.

Rachel founded SeeChange Initiative in 2018 in response to the tuberculosis epidemic in Inuit communities in the Canadian Arctic. In a culture still reckoning with the impacts of residential schools and tuberculosis sanatoriums, notes Rachel, a trauma-informed response is crucial. “People won’t go to health centres because they don’t trust the medical system — and with good reason.”

SeeChange Initiative co-designed a series of community-led, Inuktitut language workshops and sharing circles that focused on the community’s understanding of and personal experiences with TB. “People needed to talk about what had happened to them: why they were sent away, why they were strapped to a bed, why they were operated on, why their baby was taken away. By the end of the week, with opportunities to speak and be heard, and with more understanding, they were more ready to take a leadership role in co-designing a TB prevention and treatment strategy. And then, when COVID-19 broke out, those same leaders were prepared to co-create a strategy to deal with the pandemic. That community didn’t have any cases for 18 months. And when COVID-19 finally did appear, they controlled it.”

By setting up community-based perpetual funds, which are owned by at-risk communities, SeeChange Initiative aims to shift crisis funding from large aid organizations to individual communities. “Local actors,” says Rachel, “are better positioned to deliver aid faster, more efficiently, and with a vastly greater understanding of local cultural contexts.”

As part of its COVID-19 work, SeeChange Initiative began building bridges between remote and Indigenous communities worldwide, and envisions expanding these networks.

“We have extraordinary activists in communities from Nunavut to Peru, Sierra Leone to Venezuela, and more,” explains Rachel. “These are the real humanitarian actors, the ones on the ground who are defending their communities and protecting them against health and climate threats at all odds. So, rather than sending a global humanitarian charity to Sierra Leone, we can imagine communities in Peru sharing their strategies with communities in Sierra Leone and in Nunavut, who can share their wisdom with Indigenous peoples in Brazil, and so on. It’s such a commonsense solution that it begs the question of why it’s not already being done.”

Highlights from the Network

Rachel Kiddell-Monroe’s TED Talk: Championing Humanity in the Face of Conflict and War

Ernest Jr. Edmond is harnessing the vigour and spirit of inner-city youth and their parents to revolutionize the youth-service ecosystem.

At LBI, personal transformation is the foundation for social commitment and creative engagement for change.

The power of sport to jumpstart community engagement

With quality training and equipment, a teen on a basketball court can master a crossover dribble or hone their reverse layup. With the same attention to training and quality, says Ernest Jr. Edmond, that teen can also learn how to become a community advocate.

At Les Ballons Intensifs, Ernest and his team combine sports training with civic engagement, empowering youth from low-income and under-served neighbourhoods to become agents of change.

Born in Haiti and raised in Montreal East, Ernest is a firsthand witness to how social inequities disenfranchise residents from community engagement. Without access to meaningful opportunities to get involved, and with no clear path to escape their social conditions, kids from his community were adopting antisocial behaviours. To many, sports seemed like the only real way out — but only a tiny percentage of kids were destined to become elite athletes.

Ernest saw a different way. At LBI, sport is a vehicle for building leadership, accountability, and community. Participating youth and their parents sign a community pact, agreeing to give it their all in both rigourous, high-quality sports training and community well-being initiatives like neighbourhood cleanups, gardening, cultural events, and development workshops. The programs are free, but the coaching and equipment — as well as the expectations — are top quality. “Your environment represents you,” says Ernest. “At LBI, we want all these kids to be the best citizens, and so we need to give them all the best services. It’s not something that should be reserved only for the elite.”

The teambuilding skills LBI youth learn on the court are channeled into community-building skills off it. LBI participants learn how to advocate for themselves, their families, and their communities: for example, generating petitions to install water fountains at local parks, volunteering at community organizations, participating on boards and school councils, even starting their own businesses and not-for-profits.

“These kids are used to seeing themselves as the problem: as the racialized kids playing basketball in the park at night and getting up to no good, as the recipients of other people’s decisions and charity,” says Ernest. “We’re changing that narrative. LBI youth are learning to see themselves as leaders. These kids are in the park, in public spaces, in bright daylight. They’re engaged, they’re meeting people in their neighbourhoods, they’re working hard, they’re smiling, they’re making a real difference — and they like it. We are redefining what it means to be engaged.”

Highlights from the Network

Young Agrarians is growing the next generation of ecological, organic, and regenerative farmers in Canada.

In a chaotic world, and in the face of climate change, we all need access to locally grown and culturally appropriate foods. By supporting new and younger farmers, Young Agrarians helps to secure that access.

Farming as applied activism

“If we want to regenerate the land, we need to regenerate farmers,” says Sara Dent.

That’s the premise behind Young Agrarians, the organization Sara co-founded in 2012 to do precisely that. In the face of rising land costs and declining numbers of Canadian farms and farmers, Young Agrarians has spearheaded a variety of innovative approaches to breathe new life into Canada’s agricultural sector.

Now the largest educational resource for new farmers in the country, Young Agrarians delivers programs across western Canada and works coast-to-coast through its networks.

The ever-rising cost of land is the #1 barrier to entry for new farmers. With land values already high, in 2021 alone, the market value of land and farm buildings in Canada rose by 22.7%. Most young farmers, Sara notes, simply don’t have access to the capital or credit to enter the market. For that reason, Young Agrarians has created a land-matching program that connects would-be young farmers with landholders, and provides free educational and legal supports to enable viable land-sharing arrangements. To date, the organization has completed close to 300 land matches on more than 11,000 acres in British Columbia, providing new farmers with land access, landholders with a means to produce food on their land, and older farmers with succession options, all while building stronger community bonds and collective knowledge. To Sara, this sharing of the land is a — literally — a grassroots form of philanthropy.

What’s innovative about Young Agrarians, says Sara, “is that it’s farmer to farmer.” Rather than bringing in industry or academic “experts” to dispense advice or technology from on high, Young Agrarians engages directly with local farmers who teach, mentor, and build community. The organization prioritizes the increased diversity of farming by creating welcoming spaces for women (who make up more than 50% of participants) and BIPOC communities, including training settler farmers in reconciliation to increase relationships with Indigenous communities.

Young Agrarians Apprenticeship Program matches “farm-curious” new and young adults with host-farm mentors in experiential training on-farms in a wide variety of settings. For those in start-up, the organization’s Business Mentorship Network has seen participating farms increase land in production by an average of 48%, revenue by 64%, and food production by 72%.

Post-pandemic, says Sara, “Young Agrarians farmers are very eager to network and exchange knowledge to help their businesses grow and adapt to climate change.

“We saw with Covid that when you don’t have short supply chains, you’re extremely vulnerable. To ensure that we have farmers in the future, and a resilient climate adapted food system, we need enough local farmers who are viable, and can weather today’s economic and climatic conditions.”

Highlights from the Network

Sara Dent, Founder of Young Agrarians on the Future of Farming

Supporting New Farmers to Address the #1 Barrier to Farming: Land

BC Land Matching Program supports access to affordable farmland

When people have the tools to learn about and monitor their local waterbodies, they are inspired to protect water and advocate for its health.

Water Rangers harnesses the power of the crowd to empower everyone to become a water steward.

One test at a time: Water Rangers crowdsources water-quality data

“Canada has lots of water, and very few people to monitor the health of that water,” says Kat Kavanagh. In fact, she points out, we don’t have basic health data for more than 60% of this country’s rivers, lakes, and streams. “And if we don’t have the data to understand the quality of our water, we can’t make evidence-based decisions about how to best care for it, or to know if things are getting better or worse.”

Kat created Water Rangers in 2015 for precisely these reasons. The organization addresses Canada’s water-information data gap by creating and distributing water-testing kits to individuals and communities, giving them the tools to test and monitor local bodies of water and — crucially — manage and share that data on an open-source platform that anyone can access.

“A lot of people feel helpless in terms of the decisions being made about their waterbodies, and stuck about what they can do to help,” says Kat. Water Rangers empowers the public to take direct, meaningful steps that contribute to the health of local water. In the process, they’re building new generations of community scientists inspired to act as water stewards.

The strategy is working: more than 80% of Water Rangers testers report that since becoming involved with the organization, they have spent more time in nature, taught others how to test water, and spoken to others about environmental protection. In partnerships with more than 200 academic, government, First Nations, Inuit, and Metis, and other community groups, Water Rangers has reached more than 25,000 people, bringing the public into spaces previously reserved for scientists and government. The organization partners with school boards and educators to integrate water monitoring into STEM learning in school boards across Canada.

Kat’s background as a user-experience designer is a driving force in the organization’s success: Water Rangers tools are attractive, easy to use, and affordable, and she’s constantly tweaking and improving them based on user input. The tests offer immediate feedback, so users can interpret the results on the spot and understand their implications.

Water Rangers’ expertise and approach is increasingly recognized: they continue to partner with universities and governments at all levels on water issues and are taking over national assessment of Canada’s watersheds via the World Wildlife Fund’s Watershed Reports for Canada.

“We imagine a world where every community has the tools to take care of the waterbodies important to them,” she says. “Every lake, river, or stream should have enough data to know whether it’s healthy.”

Highlights from the Network

Water Rangers has partnered with Dr. Kerri Finlay to fill the gaps in accessible water quality data

HeroWork’s “Radical Renovations” dramatically cut renovation costs. They’re also spectacular community events that build community, connection, and capacity for change.

Renovating a single charity impacts many people. Renovating many charity buildings impacts a community. Replicating HeroWork’s programming throughout Canada can change a nation.

Renewing Canada’s charitable infrastructure

HeroWork began because Paul Latour wanted to help a friend with multiple sclerosis make her home more accessible. “Originally, I thought I’d call up a group of friends, order some pizzas, and do some work.” But the idea morphed into something bigger. Seven weeks later, with a team of 20 volunteers, he spearheaded a single-day, $25,000 renovation project with a budget of only $380.

That project galvanized Paul. He’d witnessed not only how a building could transform someone’s life, but also the tremendous power of community to create change.

He also recognized that the food banks, shelters, counselling centres and other buildings that served the most disadvantaged people in his Victoria, BC, community often needed urgent repairs. In many instances, the state of a charity’s building hindered its ability to provide basic services, let alone innovate and improve.

So, Paul created HeroWork. The organization identifies and collaborates closely with local charity partners whose mission and vision would be strongly enhanced with infrastructure upgrades. HeroWork then creates unique, curated “Radical Renovation” events that pull together a wide range of stakeholders — neighbourhood residents, small-business owners, construction companies, charities and their clients — who provide pro bono expertise and labour and discounted materials.

Much more than nuts-and-bolts construction projects, Radical Renovations are inspiring and energizing community events.

“Think of a modern-day barn raising or extreme makeover event, with up to 100 people working simultaneously in colour-coded T-shirts, with lunch served by hotels and restaurants, accompanied by local live music,” says Paul. The idea, he explains, is to create a powerful, tangible experience that connects local businesses and volunteers more closely with charities in order to create a more empathetic community.

At the same time, the renovations transform the way the charities use their buildings, providing them with the spaces they need to creatively deliver their services and nurture innovation.

To date, HeroWork has completed millions of dollars’ worth of charity renovations in the Victoria area, mobilizing hundreds of companies and thousands of volunteers, with a cumulative impact on more than 25,000 individuals and families each year.

Now, Paul plans to expand the organization across Canada, creating new chapters and empowering community-minded leaders to draw on HeroWork’s expertise, track record, strong brand, and powerful business systems as they organize and complete Radical Renovations. In the process, he’s building stronger and more empathetic communities with greater capacity to serve vulnerable populations.